I’m giving a talk next week on my experiences in Kenya. So I have been thinking even more about my three visits to that country and how my attitude has changed over that time. My talk will focus on three woman I have known and worked with, and how their personal stories tell much of the story of the country. In April, Kenya amended its marriage laws to legalize polygamy, further undermining the position of women in that culture. In a country struggling with over-population, never mind deep inequality, this is a undeniable backward step for all. When the bill was passed, the BBC reported that the female MP’s walked out of parliament claiming, “that a decision to take on another wife would affect the whole family including the financial position of other spouses.”

After my first time in Kenya, my friends and family organized resources to support a bright young unqualified teacher to help her attend university and the wave continued in that circle to support four students in high school. Education is costly even at the high school level, and studies document the undeniable positive effect of education on the society as a whole. Here is an excerpt from Nicholas Kristoff’s op-ed piece in the New York Times Sunday Review, May 10, 2014.

That means that curbing birthrates tends to lead to stability, and that’s where educating girls comes in. You educate a boy, and he’ll have fewer children, but it’s a small effect. You educate a girl, and, on average, she will have a significantly smaller family. One robust Nigeria study managed to tease out correlation from causation and found that for each additional year of primary school, a girl has 0.26 fewer children. So if we want to reduce the youth bulge a decade from now, educate girls today.

More broadly, girls’ education can, in effect, almost double the formal labor force. It boosts the economy, raising living standards and promoting a virtuous cycle of development. Asia’s economic boom was built by educating girls and moving them from the villages to far more productive work in the cities

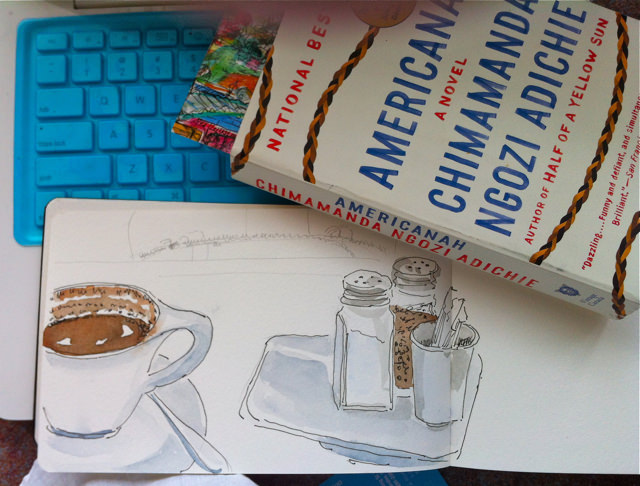

While the support for education is positive, I am now thinking beyond that. Much more must be done working with the people of Kenya and taking our lead from them. I’ve talked here about the hopeful beginnings of a small cooperative in Matangwe Kenya making hooked rugs. It could be a way for women to earn, to be in charge of their own incomes and to make decisions about how they spend that income. My thinking has changed radically from my first visit when I loaded my suitcase with donations for the school. I realize now that these ‘one-off presents’ are short-lived and encourage the thinking that someone else will solve the problem. The Nigerian protagonist’s comments on charity in Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s striking, eye-opening novel, Americanah, (a novel I encourage you to read), clarified a growing discomfort I have had with providing and deciding instead of listening and facilitating.

A couple spoke about their safari in Tanzania. “We had a wonderful tour guide and we’re now paying for his first daughter’s education.” Two women spoke about their donations to a wonderful charity in Malawi that build wells, a wonderful orphanage in Botswana, a wonderful microfinance co0perative in Kenya. Ifemelu gazed at them. There was a certain luxury to charity that she could not identify with and did not have. To take ‘charity’ for granted, to revel in this charity towards people whom one did not know–perhaps it came from having had yesterday and having today and expecting to have tomorrow. She envied them this…Ifelelu wanted, suddenly and desperatley to be from the country of people who gave and not those who received, to be one of those who had and could therefore bask in the grace of having given, to be among those who could afford copious pity and empathy…

It’s complex to state it mildly. These are some of the questions I am grappling with–I hope with open eyes and ears.

Leave a Reply